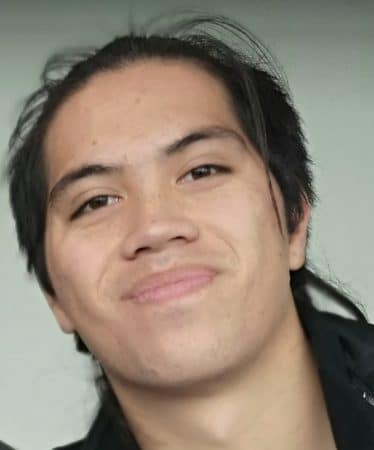

Ask Tahuaroa Ōhia to describe the relationship between his father and him and the word taonga springs readily to mind. Altogether Autism delves into what he means.

HAMILTON AIRPORT seems an odd place to meet to talk about the relationship between Wellington-based father and son Bentham and Tahuaroa (Tahu) Ōhia.

But the opportunity to chat to them face to face about what is clearly a special bond is too good an opportunity to miss.

It was the 50th birthday party for Bentham’s brother that brought the whānau – wife Kate Cherrington and daughter Tuakoi, 23 – back to the Waikato for two days from Wellington and Auckland respectively.

They are a close-knit family unit clearly proud of Tahu, 20, who was diagnosed with autism when he was six, back in 2005.

The diagnosis came the same year Bentham took up a job as Te Wananga o Aotearoa chief executive in Te Awamutu. The family were living in Tauranga at the time and the challenges of a new job meant his availability to participate in the many meetings needed to establish a route forward for Tahu were limited.

Bentham had no idea what autism was when the diagnosis came. “I didn’t really understand what it was at the time. But then gaining an understanding of it made me think about a lot of people I met in my life who had similar characteristics so it raised my consciousness around wanting to, with Kate, Tuakoi and whānau, create pathways that would be more enlightening for Tahu.”

It was the empowering role education has which became important to Bentham and Kate for Tahu as they are both committed to education as the answer to life. They work in it and their opinions are readily sought by sector groups and politicians.

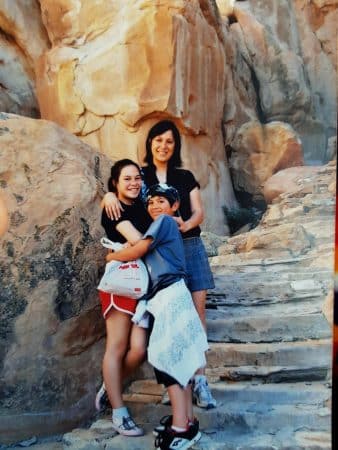

LOOKING BACK: Tahuaroa Ōhia with his sister Tuakoi and mother Kate Cherrington.

Tuakoi knew her brother was unique from other kids.

“When I was younger it was a bit hard for me to understand him. Once he was diagnosed, that didn’t change the way I saw him. I’ve always been protective of him.”

Giving Tahu the opportunity to shine and rise above the challenges life as an autistic represents is something Bentham valued then and now and is something Tahu values in his father.

“I really wanted my Dad to get to know me a little bit more, but he has to try and put food on the table and clean the car etc.

“That was sad because I really wanted him to be part of our childhood, he was just far away. His body was in another place, his spirit, his wairua was definitely there for me though. With other fathers, they would want to take their presence and spirit with them.

“Give him credit. Some other dads would want to get out of this commitment. I don’t really know what other dads think about autism ….. there are some parents who are useless and there are some that are natural. Dad’s a natural.”

The two have their differences. Tahu is into cult geeks, comics and movies. Bentham loves his rugby and helping communities.

Asked what advice he would give to other fathers struggling to understand autism and how to respond, Tahu says: “Don’t be scared of your kids because what you made right there is really special. You made a taonga.

Give (your relationship) a try, don’t walk away.”

Seeing this confident, well-spoken young man now and it is hard to visualise him as a child whose only way of communicating was by using a single word, Rex. The answer to every question was Rex.

Tahu’s brain was processing plenty though. He knew all the words and actions in the American animated science fiction film The Iron Giant. He mimicked the character’s movements at every opportunity. He was into dinosaurs; hence he loved the word Rex as in tyrannosaurus rex.

“I didn’t know how to spell hello, which was really unusual for the teachers, or goodbye, or how are you doing. I did not know how to put them into sentences.

“Teachers would say: ‘Can you spell a word?’ I’d just spell Rex, because I’m into dinosaurs.”

He was fluent in Te Reo Māori though.

IN PURSUIT OF TE REO: Tahuaroa and Bentham Ōhia are both on an education journey.

He pays credit to his family and teachers for their support.

“I had a lot of help from teachers, I did have a lot of help when my Mum said I was diagnosed with autism, they had to get to know me first and then put me in a space where I could be myself around other kids. I did scream, I did kick, I did push away some of the kids back in the day. I didn’t want to hurt them like the Hulk. I just wanted to be left alone in my own world. I just wanted to protect myself in my own world.”

The pursuit of education became a driver for him particularly because some teachers and doctors said they did not know if Tahu was smart enough to get through school or would have to be held back in class.

Today he is two years into a diploma in performing arts at Te Auaha Whitireia in Wellington. Once he gets his diploma, he will switch and study musical theatre aiming to get a bachelor’s degree so he can become an indigenous film director. He wants to put indigenous people into short films to learn about their histories, their stories.

“Achievements are not a one-time thing. Every challenge has an achievement and every achievement doesn’t come once, it comes in many ways. You can achieve by opening a jar.”

Autism is who he is, says Tahu.

“To be honest, I’m happy. I know I had a rough childhood trying to get through this challenge, trying to process my brain.

“Guess where I am right now. I’m still going through challenges with my autism at school and at home. But at least I got through them. There are heaps of challenges out there.

“I did achieve. I achieved on speaking, on trying to communicate, but the really cool thing about achievement is I’m still alive today. If I fail, I still get through the day.”

- Tahu’s tribes are Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Pūkenga (Mataatua Waka) Ngāti Ranginui (Takitumu Waka), Ngāti Te Roro o te Rangi (Te Arawa Waka), Te Āti Awa (Tokomaru Waka), Ngāti Rārua (Tainui Waka) and Ngai Tahu (Takitumu Waka), Ngati Hine, Nga Puhi and Ngāi Pākeha.

- This article first appeared in the Altogether Autism Journal, Issue 2, 2019