When David Taylor talks about his children, be prepared to go on a journey of autism discovery.

All five of his sons are autistic and each is quite different, plus, about three years ago, David himself was diagnosed with high-functioning autism and 13 years ago diagnosed with dysgraphia (a neurological condition where a person has difficulty with writing).

Under emotional and academic pressure, the 50-year-old Auckland-born house husband struggles. He cannot spell and his writing is poor.

“I’m like a really messy filing cabinet. My thought process is different, it takes a little bit longer for me, but I get there,” he says.

He needs to “get there” because the challenges he and his wife Justine must deal with daily, would test even the most efficient or methodical person.

Wind the clock back and David is 15, living on Waiheke Island and about to drop out of high school with no qualifications. His family life was dysfunctional, both parents were alcoholics and one of his three brothers had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) which resulted in him taking his frustration out physically on David.

David met and fell in love with Justine as a teenager. They split and went on to marry other partners. Justine had two boys – Matthew, 19, and Hayden, 14 – both on the spectrum.

Before David married, unbeknownst to him until some years later, he had a son, Jonathan, now 28, on the spectrum, and living in Christchurch.

His only son from his first marriage, who won’t be named, is now 18 and a high-functioning autistic.

Both marriages broke down and the childhood sweethearts found each other again, married and nine years ago had Benjamin, who completed the picture by also being diagnosed as autistic.

“We’re a blended family. It’s fair to say life’s a little complicated.”

Three of the boys – Matthew, Hayden and Benjamin – live at home with David and Justine in rural north Waikato.

Justine is often away from home as she works as a facilitator, providing professional development (including special needs and literacy) for teachers and schools across New Zealand.

David’s main interests outside of his family are martial arts – he has a taekwondo black belt third degree – and mentoring.

The constant battles with various services, organisations and people who view David and Justine as “atypical parents with atypical personalities” means life is never dull.

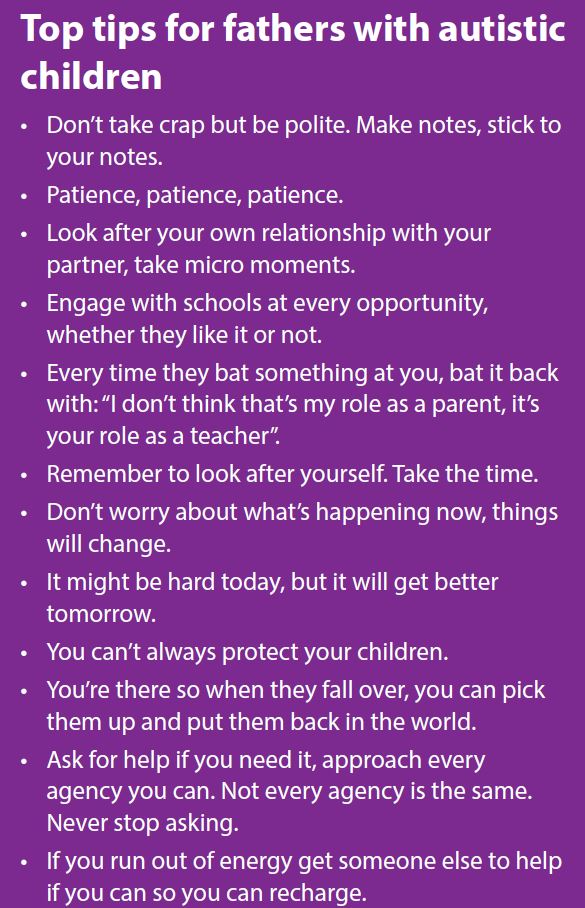

Battling with multiple organisations for each child to gain support became exhausting and traumatic. Repeatedly retelling their story, coordinating appointments, sitting on waiting lists for lengthy periods, experiencing judgement from professionals, lots of talk around the table resulted in very little practical support. David feels the turning point came when both Justine and David made the decision to disengage from these organisations to manage the boys themselves.

“It can be tough at times but there is hope. Our kids get to a good place in their own time and in their own way,” says David.

Removing societal expectations/pressures is vitally important for neuro-diverse people.

“Life becomes easier when we allow our family to develop at their own pace.”

David supports the boys with their daily life by advocating on their behalf. This includes engaging with doctors, chemists, teachers and the world when out in public.

“While advocating for our children in schools is challenging as you become labelled as a difficult parent very quickly, it is important to remain an active advocate throughout their schooling as they need you to do this within our current school system.”

David emphasises that Justine’s support to understand how schools and teachers work has been invaluable in making advocacy with schools successful.

DOG GONE: Great Danes Ava and Noah are great companions for David Taylor and his family.

“It is very important to build respectful relationships and work collaboratively with schools while advocating for your child.”

In 2018, Hayden and Benjamin both started at Whitikahu School, northeast of Hamilton, a 90-roll country school for years 1 to 8. * See Education Review Office comment below.

“They have been amazing. They provided an environment for Hayden to succeed and now Ben is flourishing there as well.

“Talk about relationship building, they are just a wonderful, inclusive, community-based school. Everybody helped.”

Matthew left high school when he was 16 unable to get anywhere in the system even though he won a cyber security competition at 15 and was awarded a full scholarship through IBM to attend Unitec.

He now works for a computer technology company and is totally self-sufficient financially. He has many online friendships and work connections with people from all over the world. Conscious of the lack of public transport in rural Waikato, Matthew is concentrating on getting his drivers’ licence.

“That will be yet another challenge,” says David.

Ben is the family ‘social aspie’ – incredibly active and chatty.

“Our mantra at home is ‘Change is Constant – we can’t fight it.’ The only thing you have control of is yourself.”

The boys need David to walk them through change and support them with this.

He is concerned about how young men generally are being taught not to be caring, to harden up, to shape up.

“I teach my men to be kind, considerate and nurturing and that it’s okay to touch. Touch is important. I teach them mindfulness.

“Hope is the main message. The world is changing, your children become adults and successful adults in whatever way is successful for them.”

- David Taylor is autistic and a north Waikato-based house husband with five sons.

- This article first appeared in the Altogether Autism Journal, Issue 2, 2019.

- Students with additional learning needs are well supported. Systems for the monitoring and tracking of students are effective. A knowledgeable special educational need coordinator (SENCO) works cooperatively with staff to provide a range of effective interventions to respond to at-risk students’ needs. The SENCO accesses specialist services for children with additional learning and/or behavioural needs. Parents are well engaged as partners in their children’s learning. – Education Review Office, 2019.