Stimming is often thought of as one of the hallmark features of autism, writes researcher Emily Acraman.

7 October 2020 – With a long history of misunderstanding and negative social stigma, growing evidence confirms these behaviours are hugely important for the neurodiverse community.

The term stimming comes from the clinical phrase ‘self-stimulatory behaviour’, also known as stereotyped behaviour. The neurodiverse community have reclaimed these technical terms, and the wider autism community now refers to this behaviour as stimming.

For an autistic person, stimming usually refers to repetitive or rhythmic behaviour that is commonly expressed through body movements (e.g. hand flapping, finger flicking, hair pulling or pinching, feet flexing, spinning, necklace playing etc) but also vocalisations (e.g. muttering, grunting, stuttering, whistling, singing) (Kapp et al, 2019).

The autistic community advocates that stimming behaviour is a self-regulatory coping mechanism, and efforts to control this behaviour could have negative effects for autistic people (Lilley, 2018). Research exploring stimming from the autistic perspective supports this position and suggests these behaviours are actually incredibly beneficial.

There is a long history in both research and clinical practice, of efforts to reduce, minimise or eliminate stimming behaviour in autistic people. Unfortunately, interventions which aim to control this behaviour remain popular (Jaswal & Akhtar, 2018).

What is the benefit of stimming?

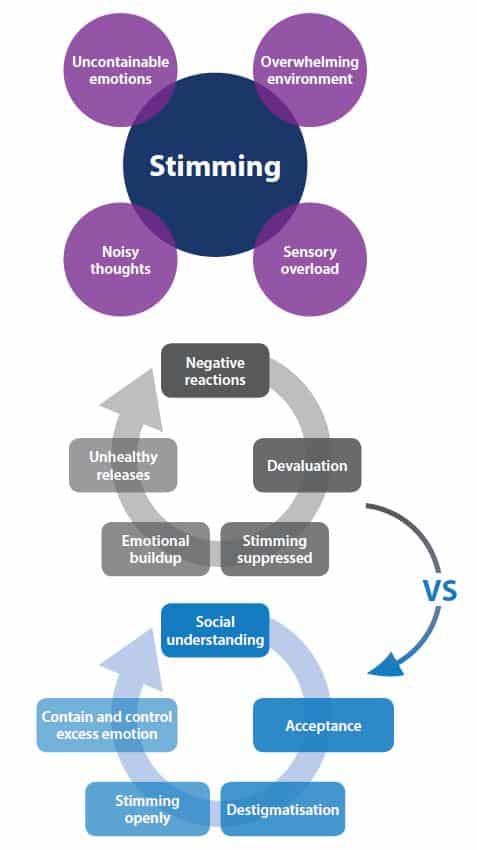

Most of the recent theories around why autistic people stim suggest that stimming provides reliable and self-regulated feedback as a response to an overwhelming, unfamiliar or unpredictable environment (Kapp et al, 2019). This includes seeking hyposensitivity (sensory seeking) satisfaction in a sensory lacking environment and hypersensitivity (sensory avoiding) relief from both excessive sensory input, and emotional overload (such as anxiety). While there isn’t a lot of concrete evidence to support this, autistic adults tell us that stimming has a far greater function than just self-stimulation (Kapp et al, 2019; Steward, 2015).

A 2015 study by Steward, which involved an online survey of 100 autistic adults highlighted a wide range of reasons why autistics stim. The most common of these being, a coping mechanism to reduce anxiety (72%), to calm down (69%) and overstimulation from sensory input (57%). Additionally, 80 percent of the study participants reported that they enjoyed stimming, nine percent reported they did not like to stim and 11 percent said it depended on the stim. Interestingly, 72 percent of participants involved in the study had been told not to stim (Steward, 2015).

A 2019 study published by Kapp et al, explored the views of 32 autistic adults regarding stimming. Researchers asked the study participants why they stim, what the value of stimming is for them, and what they feel about other people’s perceptions and reactions to their stims. One of the key findings of this study was that although participants said their stims were automatic and uncontrollable, no one reported consistently disliking them. Further, most people described their stims as pleasant and calming.

When asked why them stim, study participants reported their stims were either a response to sensory overload, or overpowering thoughts. The autistic people in this study reported they were often overwhelmed by sensations, new information or their own thoughts. Stimming acted as a self-regulatory coping mechanism which helped them to feel calm and in control. While the study participants reported beneficial and meaningful purposes for their stims, the majority also described encountering negative social judgements from people which made them feel rejected and self-conscious about stimming around others (Kapp et al, 2019).

Conversations around stimming…

It is clear through conversations with parents of autistic children and autistic adults, that stimming serves a necessary and meaningful purpose for the autistic individual. I spoke to a parent of a 10-year-old non-verbal autistic boy. She talks about her son’s stimming as his own unique way of communicating his emotions. While many children of the same age can struggle to find the words to capably express their inner thoughts and feelings, stimming for an autistic person prevails where words fall short. This parent celebrates her autistic sons stims, as it gives her and those close to him a visible and definitive understanding of how he is feeling in a particular moment. His family, friends and teachers have learnt to recognise his stims and what they mean and what he is trying to communicate. His stims are a combination of hand flapping and vocal stims whether he is happy or upset. The difference is the intensity in which he stims. When he is happy, he flaps his hands with hands open and arms out and vocalises joyful, excited noises. When he is experiencing strong negative emotions, he flaps his hands more rigorously, keeping them closer towards himself and vocalises more distressed sounding noises. His family say they like that his stimming is his way of communicating with the world around him, he just expresses himself through his body rather than his words.

Another parent talks of her 11-year-old autistic daughter’s verbal stims. While some people refer to them as tics, she believes that from an outside perspective they seem to serve a different purpose. Tics are sudden in-voluntary behaviours or mannerisms. They do not serve a purpose and are usually disliked by the person displaying them and often associated with stress (Lilley, 2017). On the other hand, a stim is a behavior that serves a direct purpose for the individual. To this parent, her daughters verbal stims look like an extension of her physical stims and serve as a regulator of her surrounding environment. They express happiness, excitement, nervousness, stress etc when a hand flap doesn’t suffice.

One autistic adult speaks of his stims in relation to energy input/output. He sees stimming as a healthy transferal of excess energy often brought about externally (e.g. through sensory bombardment) or internally (e.g. through a flood of thoughts). He explains that suppressing stimming techniques will inevitably lead to unhealthy releases, such as anger or physical outbursts.

Moving towards acceptance

While there is clear evidence of the benefits of stimming for autistic people, many autistics still report experiencing negative social stigma and judgement surrounding their stims. Potentially this may also be why treatments and interventions to control or reduce stimming remain popular. Autistic adults and researchers in this field, however, highlight that this approach is misguided as “it strips people of a key means of coping” (Kapp, 2019).

When stimming involves self-injury, then intervention is often necessary. However, in most cases rather than focusing on interventions to reduce or control an autistic person’s stims, the focus should be on supporting understanding and awareness of others (non-autistics). It is important anyone supporting an autistic person finds and understands the balance between acceptance and change.

Autistic people tell us that rather than discouraging or trying to control their stimming, families and professionals could instead look at why the autistic person might be stimming in the first place. For example, is the person having difficulty processing sensory input? Are they feeling anxious or overwhelmed in certain situations? Is the person using their stims to communicate excitement and joy?

Navigating the neurotypical and sensory world can be hugely overwhelming, and stimming provides a practical and reliable means to calm and self-regulate.

Overall, society’s understanding holds a real key to the social acceptance of stimming. It is important we take the autistic person’s lead by accepting these behaviours and understanding the fundamental benefits they have for the individual (Kapp, 2019). Hopefully greater awareness of autistic people’s experiences with stimming may help to transform social stigmas and lead to a greater understanding and acceptance.

- Emily Acraman is a researcher for Altogether Autism.

- This article appeared in the Altogether Autism Journal, 2021

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Deweerdt, S. (2020). Repetitive behaviors and stimming in autism, explained. Spectrum News. Retrieved from https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/repetitive-behaviors-and-stimming-in-autism-explained/

Jaswal, V.K., & Akhtar, N. (2018). Being vs. appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2018, 1-84

Kapp, S. (2019). Stimming, theraputic for autistic people, deserves acceptance. Spectrum News. Retrieved from https://www.spectrumnews.org/opinion/viewpoint/stimming-therapeutic-autistic-people-deserves-acceptance/

Kapp, S.K., Steward, R., Crane, L., Elliott, D., Elphick, C., Pellicano, E., & Russell, G. (2019). People should be allowed to do what they like: Autistic adults views and experiences of stimming. Autism, 23(7), 1782-1792.

Lilley, R. (2017, August 25). What’s in a flap? The curious history of autism and hand stereotypies. Neurosocieties Symposium: Explorations of the brain, culture, and ethics, Monash University. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326147015_What’s_in_a_flap_The_curious_history_of_autism_and_hand_stereotypies

Steward, R.L. (2015). Repetitive stereotyped behaviour or ‘stimming’: An online survey of 100 people on the autism spectrum. International Meeting for Autism Research. Retrieved from: https://insar.confex.com/insar/2015/webprogram/Paper20115.html