As a parent or caregiver, having your child wander off, or going missing can be one of the most nerve-racking experiences. For parents of children with autism, many know this feeling all too well, writes Altogether Autism researcher Emily Acraman.

2 April 2020 – STATISTICS REVEALING the prevalence of wandering or running behaviours among autistic children highlight just how common this issue is for many of our families who support or care for an autistic person.

Some studies report almost half of autistic children have wandered off from a safe environment (Anderson et al, 2012).

Wandering or ‘running’ occurs when a person leaves a safe area, or a responsible caregiver. It is usually an impulsive behaviour that is distinct from typical age appropriate behaviours, such as when a toddler may run off from a parent. It normally lasts for more than just a moment and has the potential to result in injury or harm.

How common is it?

A 2012 study involving a US community-based sample of more than 1200 children with autism found that nearly half of parents (49 percent) reported their child with autism had attempted to wander or run away at least once since age 4. Of those children, 53 percent had gone missing long enough to cause worry. Additionally, 65 percent of wandering incidents involved a close call with traffic, and nearly a quarter (24 percent) involved a close call with drowning (Anderson et al, 2012).

Similarly, a 2016 study involving more than 2000 children with autism and/or intellectual disability found wandering behaviour among autistic children regardless of intellectual disability is relatively common. They reported 37.7 percent of autistic children and intellectual disability and 32.7 percent of children with autism and no intellectual disability had wandered or become lost in the past year (Rice et al, 2016).

Who wanders and why do they do it?

Autistic children wander for a variety of reasons and under several different circumstances. Sometimes they may run off to reach a place they enjoy, or they may run to try and escape an overwhelming situation or sensory overload.

Parent reports tell us the most common reason their child wanders (53 percent of the time) is because they simply enjoy running and/or exploring (Anderson et al, 2012).

Often the behaviour is goal oriented, and there have been a few small studies conducted using functional assessment based behavioural interventions which have successfully reduced wandering behaviour (Anderson et al, 2012).

The most common locations from which children wander vary in the published literature, but these generally include; a shop or public place, the child’s or someone else’s home – and school.

Studies exploring characteristics of children who wander found that generally, wandering increased with autism severity. Additionally, the child’s experience while wandering and the motivation behind the behaviour also differed depending on autism severity.

Children with more severe or classic autism tended to be happy, playful or exhilarated when wandering, whereas children with higher functioning autism were more likely to be anxious, sad or confused (Anderson et al, 2012).

Importantly, research has also determined that autism related wandering does not come from inattentive or ‘bad’ parenting. Wandering has little to do with parenting style, socio-economic status, or education level, and is more to do with the nature of a child’s autism (Anderson et al, 2012).

Unfortunately, one of the reoccurring themes throughout the literature regarding autism related wandering is that parents felt they received little to no support or information from professionals around ways to prevent or manage their child’s behaviour (Anderson et al, 2012; Solomon & Lawlor, 2013).

Further, while some studies have indicated that the use of prevention measures for wandering are relatively common among parents of autistic children, details on what was done, and whether the measures were effective are lacking in the published literature (Rice et al, 2016).

In response to requests from parents, here is a list of strategies families and caregivers could consider if they are concerned about their child wandering from a safe place or person.

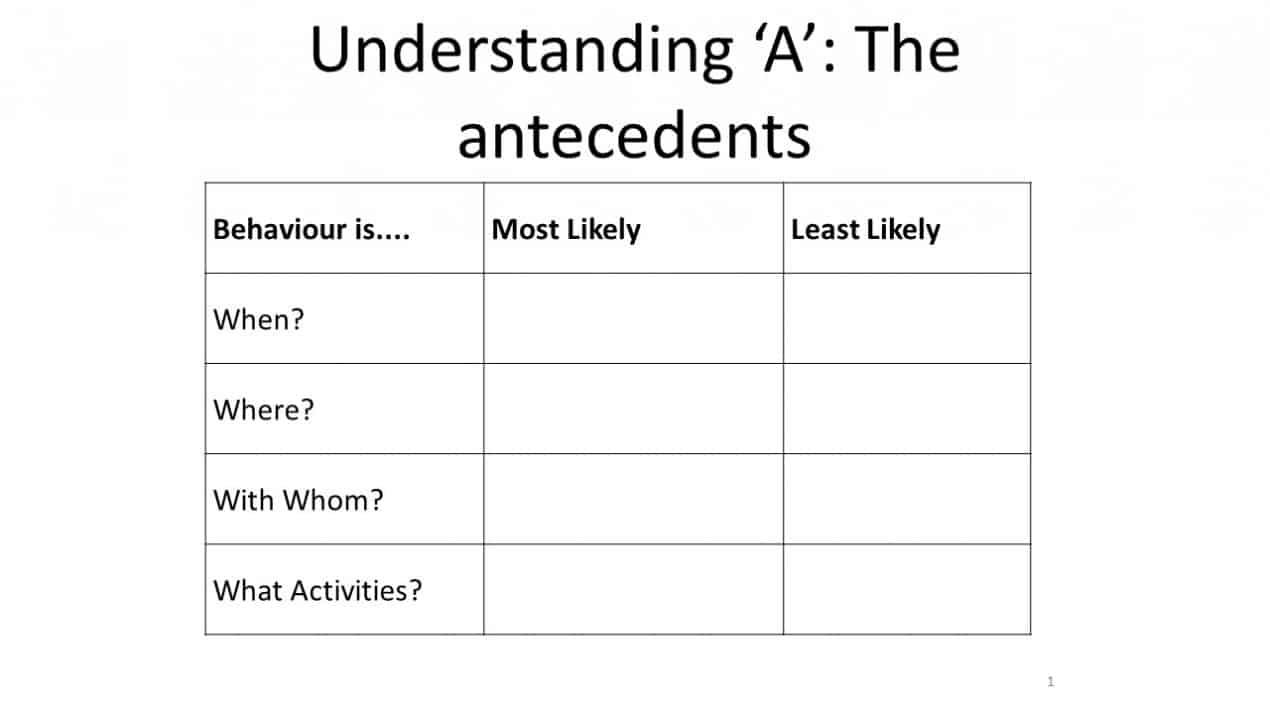

Top Tip #1 – Understanding why the behaviour is occurring

- Often children have a reason for wandering: to escape, to seek out something they enjoy etc.

- If the reasons are unclear consider keeping a ‘wandering log’ with details such as when the behaviour occurred, what events lead up to the behaviour? Who was there? Were there any triggers present? Where did your child try to go, or what were they seeking out?

- Once the behaviour is better understood, you can then develop strategies to address the needs, before the behaviour occurs.

- Professionals such as behavioural therapists, and psychologists with autism experience can help to understand why this behaviour is occurring, and how it could be prevented or managed.

- Contact us for recommended professionals in your region.

Top Tip #2 – Communication of contact information

- One of the ways to do this is to teach your child their contact information, e.g. name, phone number or address.

- For children who are not able to communicate this, alternative options could include:

- Temporary safety tattoos with contact information so Safety Tat or Tattoo Ads

- An ID card which the child could give to adults when necessary

- Medical ID bracelets or necklaces

- Clothing or shoe tags

- Ice ID

- Personalised labels Stuck on You

- MediBand

- If your child is sensitive to items on their body, you may have to employ some creative solutions which fit your child’s preferences.

- Safety tip: for identification products (tattoos, bracelets etc) it is recommended that you don’t include your child’s name, as you do not want to display this to strangers.

Top Tip #3 – Secure the Environment

-

- Alarm or secure your home. For children who tend to walk out the door or escape through windows there are a number of different home security systems on offer, such as- a monitored alarm, or special locks.

- Fence your property or an area on your property and talk with the school about whether the school grounds are fenced. You may be eligible for Ministry of Health funding for certain housing modifications to your home. See the Whaikaha | Ministry of Disabled People website for more information.

- Alternatively, some people have found having visuals such as ‘stop signs’ on all the exits in the classroom or at home are useful in reducing the chances of their child wandering.

Top Tip #4 – Consider a GPS or tracking device

- These days there are several location devices available, some of which have been designed specifically for autistic children who are at risk of wandering. Below is a selection of what is currently on the market:

- Wandering Kiwi have a range of bluetooth devices Wandering Kiwi

- Spark offer a GPS watch Spark watch

- Spacetalk watches

- Sentinel watches offer a couple of gps trackers Sentinel watches

- HereO offer a GPS watch HereO

- Location Tracker App

- Angelsense offer a GPS tracker designed out of necessity by a parent with an autistic child Angelsense

- Please note, Altogether Autism cannot specifically recommend any brand or device, but these are some of the options we have found that are available within New Zealand.

Top Tip #5 – Practice with your child what they should do if they are lost

- Develop some strategies on what your child should do if they are lost and practice them regularly, especially before an outing where there could be a risk of them running.

- A good way to teach this is by using social stories. Strategies could be as simple as teaching them to stay where they are if they become lost. Read Joanne Lawless “If I Am Lost”

Top Tip #6 – Develop an emergency plan

- Having a plan in place with what to do and where to start if your child does go missing is a good idea. A thorough emergency plan should include:

- Contact details for your local police, neighbours or any places you child might go

- Your contact details

- Your child’s name, photo and description

- Places your child may go to, or things they may seek out

- If they normally wander from the same place (e.g. your home or school), a good idea would be to include a google map of the area highlighting any places of possible interest or dangerous areas

- Information about how your child may react to people they don’t know or to being lost.

- Share the plan with your child’s school and any key people in your safety network.

• It is also a good idea to talk with the school to see what plan they have in place if a child is to go missing from their grounds.

• Safety tip: be mindful about who you share this information with and where you keep this information stored. You do not want personal identification information in the wrong hands.

Top Tip # 7 – Establish your safety network

- If your child does go missing, do not try to search for them on your own. Develop a safety network of people who could help you look and who you can educate about your child’s behaviour before an emergency happens.

- This could be teachers, neighbours you know and trust, friends, grandparents etc.

- If an emergency occurs and your child does go missing, be sure to call 111 immediately.

- It may also be a good idea to contact your local police station to see if they hold information on children who are likely to go missing.

- Emily Acraman is a researcher for Altogether Autism.

References

Anderson, C., Law, J.K., Daniels, A., Rice, C., Mandell, D.S., Hagopian, L… (2012). Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 130(5), 870-877

Rice, C.E., Zablotsky, B., Avila, R.M., Colpe, L.J., Schieve, L.A., Pringle, B…. (2016). Reported wandering behavior among children with autism spectrum disorder and/or intellectual disability. The Journal of Pediatrics, 176, 232-239.

Solomon, O., Lawlor, M.C. (2013). And I look down and he is gone: Narrating autism, elopement and wandering in Los Angeles. Social Science & Medicine, 94, 106-114.

Raising Children Network. (2017). Wandering: Children and teens with autism. Raising Children Network. Retrieved from: https://raisingchildren.net.au/autism/behaviour/common-concerns/wandering-asd

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (2016). Autism: Wandering Tips.

Hyman, S., & McIlwain, L. (2019). Keep kids with autism safe from wandering: Tips from the AAP. American Academy of Pediatrics. Retrieved from: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/Autism/Pages/Autism-Wandering-Tips-AAP.aspx

National Autism Association. (n.d.) Be REDy Booklet for caregivers. National Autism Association.