Mary Anne Gill

14 March 2017 – French writer Josef Schovanec’s biography describes him as an ‘activist for autistic people’. “What does that mean?” Altogether Autism editor Mary Anne Gill asked him in Wellington where he is living for five months as the 2017 laureate of the Randell Cottage Residency.

JOSEF SCHOVANEC wanted to become a lecturer in philosophy but instead he travels the world attending conferences, appears on radio and television to shed light on what it means to be a person with autism and writes constantly.

In France, where he was born on 2 December 1981 to Czech parents, he is a media personality.

So what brings him to New Zealand for five months when the bulk of his work is in Europe?

Schovanec is researching a fictional book about an autistic friend’s journeys and research in the Pacific, a slight change in direction for the writer, polyglot (a person who knows several languages) and activist whose four other biographical books included the first memoir by an autistic person released by a major French publisher.

Securing a Randell Cottage residency and living in Wellington until June 2017 gives Schovanec something he looks forward to – relief from the thousands of emails he receives about autism.

“I hope it will help me handle my exhaustion too,” he says.

This is the first time Schovanec, who speaks several languages including English, has ever lived in an English-speaking country. An impatient publisher back home in France is not making it easy for him to relax though. There are deadlines for the three other books he is writing.

However, he has made a commitment to himself to expand his linguistic skills to include Maori.

“I would like very much to learn Maori. I don’t think I will become a fluent speaker but in four to five months, I could get to a nice level,” he says modestly.

NINE TO NOON: Josef Schovanec with RNZ’s Kathryn Ryan

Writing in Maori appeals to him too. “Maori delivers you from the painful dilemma of having two consonants next to each other.”

That journey to learning Maori started on Waitangi Day when he attended the celebrations at the Treaty grounds in Northland and stayed in Russell.

He also added 10 extra pages in his mind to his latest book about autism because of his experiences there.

He describes his social skills as poor and his understanding of certain situations bemusing even though he is clearly a bright man.

“I arrived to the hotel in Russell and there was a very nice gentleman greeted me there. ‘Are you here on your own?’ and so I said yes. He asked me a second time and I thought he was asking me because I am kind of a hero – from Europe to Russell.

“It’s only later I understood because I was dressed like an official and Russell is a holiday resort where you’re not supposed to go there on your own.

“I need to change my clothes to the place I am. It’s a great skill people have but I don’t have.”

Schovanec was born in Charenton-le-Pont and has an older sister.

“I felt I was special from the very beginning. The first physicians my parents took me to thought I had a form of schizophrenia. They treated me for that but the medication was not appropriate.”

France, and many parts of Europe, were very backward (back then) in their understanding of autism, he says.

“The majority of people with autism in France at that time had this type of negative experience.”

Schovanec’s parents were both well educated and that made a big difference for him.

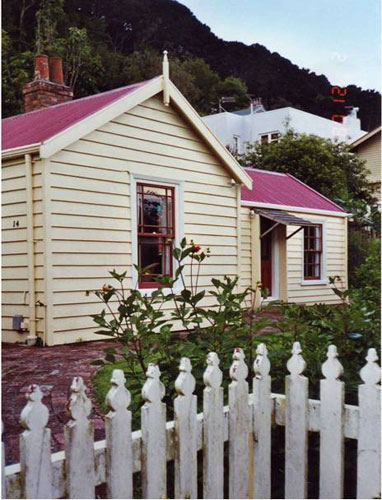

RESTORED COTTAGE: Wellington’s Randell Cottage, Josef Schovanec’s home for five months.

Partly home-schooled, he was able to learn maths from his mother because she was an engineer.

And by staying at home, he could read the many thousands of books his parents had.

By the age of seven, he could speak fluently in French, Czech, Finnish and English.

In later years, he added German, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Persian, Amharic, Azeri, Azerbaijani and Ethiopian.

“I could attend school but not all the time. School was almost unbearable for me. I could not go to the canteen; I have never eaten at a canteen.

“I was lucky with my parents. Other parents would just break and give up, particularly at that time (late 1980s). Parents were under such big pressure. All the physicians wanted to take your child and put them into a mental facility to cure that child.

“My parents never, ever accepted them. They tried their best to keep me partly at school,” he says.

On top of that, his parents had to find a solution for their son’s problems with food.

“90 per cent of children with autism have similar difficulties,” says Schovanec who goes on to reveal his food of choice for several years was spaghetti with sugar.

“People would think I was crazy. My parents love Italy and speak Italian very well so several times during my childhood they took me to Italy.

“Imagine being in a proper Italian restaurant and you order spaghetti with sugar. I have very vivid memories of some of those episodes. Once I was in a restaurant and one of the employees was begging me to eat something else. I was crying, yelling. I wanted spaghetti with sugar. “

He no longer only eats spaghetti with sugar but going to a restaurant is still almost impossible for him.

By his high school years, Schovanec’s maths was so good he considered becoming a mathematician but instead graduated from Sciences Po University (Paris Institute of Political Studies), an elite institution whose alumni numbers four French presidents, 13 past or present French prime ministers and the founder of the modern Olympics, Pierre de Coubertin.

His social skills did not improve though and the medication he was on for schizophrenia meant he was sleeping all the time.

It was not until 2007 that he received a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome and that is when he became involved in autism awareness campaigns becoming a celebrity on radio, television and print.

His first book, the best-selling Je suis à l’Est! written in collaboration with Caroline Glorion, was an autobiography, which reflected on the differences between non-autistic people and persons with autism.

AUTISTIC ADVOCATE: French-born media personality Josef Schovanec feels his social skills are getting better.

Parents of children with autism seek him out relentlessly thinking he has been successful in managing his autism.

“Sometimes they say to me ‘I am so glad my daughter or son is on the spectrum. I don’t have to worry about drugs.

“Actually they are wrong about me, they are mistaken and they usually notice it very quickly because actually I am not successful. I am as backward as their child (is).

“For instance, I cannot drive a car, I’ve never been to the hairdresser, I’ve never been to a night club. There are many things that I cannot do. Many people with autism are more skilled than me.

“What I’m trying to do is speak about all my friends.

“99 per cent of the people I meet on the spectrum don’t want to talk about autism.”

While he does travel a lot, it is something he still finds difficult.

“You learn about the airports and where the good hotels are. I don’t mean five stars, good by my standard.”

He can write anywhere, never in English, usually in French or German. None of his books has been published in English because he says the English-speaking world is more advanced in the field of autism and there are thousands of books.

The experience in Waitangi and a trip to Cape Reinga gave him many ideas for his books.

Josef Schovanec

“The colours, the different kinds of blues. The spiritual side.”

He finds his social skills are getting better but still probably lower than what people expect and believe of him.

“I’m not really good at relationships. I don’t have a vibrant social life. I never know what is the definition of a friend. Anyone who is nice to me and smiles and says hello – he or she is a friend but that can lead to great trouble. That’s what happened to me in the past. I’m protected in France and in Europe. Nobody in the autistic community would harm me.”

Schovanec is adamant there is no link between vaccinations and autism but is unable to come up with a cause.

“I do hope nobody ever finds the cause because we need autistic people. How sad would our universe be without all those great people.

“There are some aspects about autistic life that are not very funny but broadly speaking, it’s not that bad,” says Schovanec.

- This article was first published in Altogether Autism Journal Issue 1, 2017 read the latest edition.

The Randell Cottage Writers Trust was established in 2001. The restored 1867 Thorndon Cottage, one of Wellington’s 10 oldest buildings, was gifted to the trust by the Price family and hosts two writers a year; one from New Zealand and the other from France. Randell Cottage is supported by Creative New Zealand, Wellington City Council, the New Zealand France Friendship Fund and the French Embassy.