As a child of whāngai/adoption, I was raised by my grandmother in Ōrākei, close to my marae. This was an environment of manaakitanga; everything we did as a whānau was underpinned with the aim of enhancing each other’s mana. It was an environment where I knew who I was, where I belonged, and above all where I felt connected.

Every morning before school, my grandmother would take me around the bays where she would teach me about my ancestors, my people and the whenua/land. I would then practice saying my whakapapa/ancestry, and whilst I didn’t realise it at the time – I fell in love with the journey of mātauranga/seeking knowledge and excelling in everything I did.

My grandmother also taught me the mana of hard work and would set me weekly tasks to achieve, like memorising my timetables. I was a very task-orientated person and enjoyed the concept of working towards a goal – doing something for a reward. I flourished in the routine-filled environment and the security of knowing the what, when, where, who and why something was happening – I always felt in control. I felt safe.

The shift

At age nine, my grandmother was starting to get older, and I was getting cheekier. It was decided that I would return to live with my biological mother, stepfather and brother. However, this was a complete contrast to the world that I was used to, and belonged to.

There was no te reo spoken, we didn’t practice tikanga, and being Māori wasn’t the thing to be. This was the first time I felt alone, without an identity and without a connection. It was then that the little voice in my head started to say, “you were given up as a baby, and you’ve been given up again, no one wants you”.

After a couple of years of hearing this message, and fuelled by a disintegrating relationship with my new family, I started to rebel and begun to get involved in a street gang. We started drinking, taking drugs, stealing, fighting other gangs and at 14, I had been expelled by two colleges and had no job options.

However, whilst this was all happening, there was one thing that I was receiving; a sense of connection, purpose and belonging. Inside the gang, we looked out for each other, we learnt from each other, there were protocols that gave the group structure and a sense of security and safety – this was what I yearned for.

At age 20, and having spent six years with my partner Aimee, we had both become involved in a world where alcohol and drug use, gangs and partying had become the norm; we were both out of control and heading towards a dead end.

Varden Turaukawa Bartlett

In 2010, Aimee fell pregnant, and even though I didn’t know it at the time, this was the beginning of the change. When Varden was born, I realised that he was the true sense of connection I had been yearning for since I was that 9-year-old little boy.

In a search for a new beginning, Aimee and I soon made the move to Perth where Aimee had whānau. I had trained as a butcher, and I found a job in a smallgoods store. There was a strict routine and structure that I loved, and before I knew it, I was offered a rent-free home and a pathway into the business.

Aimee was able to stay at home to look after Varden, and at 18 months, he could say mummy and daddy, he was a smiling, happy and a ‘normal’ little boy – life was perfect!

Turaukawa Bartlett with his son Varden.

The change

I can remember it like it was yesterday. It was a normal day, and just like any other I opened the door and went up to Varden expecting the normal smiling response. However, this time something was different. There was no smile, no hug, no sounds, no eye contact, nothing. It was as if someone had taken my boy and left an empty shell – we knew something wasn’t right.

Shortly after, we started noticing a few different things like the tippy toes, the flapping, the stimming noises and an overall sense of disconnection.

As time went on, Aimee and I reacted differently. Like many parents, Aimee started consulting ‘Dr Google’ and researching everything she could to find answers, whilst I chose the easier route – denial. I didn’t want to accept that my little boy was different or that there was something wrong.

At 30 months old, Varden was diagnosed with severe autism. The little voice in my head returned, but this time the message was “this is your fault, you’re a failure as a dad, not even your son wants you”.

To help deal with the voices, I turned to what I knew would help – alcohol. For the next year, I started drinking heavily again, and as Varden’s symptoms worsened; the meltdowns and late-night screaming matches, so did the fracturing of my relationship with Aimee. It got to the point where I started asking those age-old questions like “why us?”, “what did we do wrong?”. I soon arrived at rock bottom, and got to a point where taking my own life had become an option; a way out.

It was then that the thought of Varden growing up without a whānau, a father and a sense of connection hit me like a ton of bricks and forced me to ask the question – “What would have happened if my grandmother had turned her back on me?”. Picturing her face, I made the decision to bring my whānau home to what I knew gave me a sense of wellbeing in my early years – whanaungatanga.

MANAVATION: Turaukawa, Aimee and Varden Bartlett at home in Karangahake Gorge.

In 2015, we arrived in Paeroa and changed our whole life to surround Varden with whanaungatanga; connection to his culture, his people and his turangawaewae – a place he could stand proud and call home.

We built connections with the amazing whānau from Goldfields school, and after a year at home, Aimee had begun her journey into becoming a counsellor. I had just started a role as a whānau support worker also as we both realised that our experiences were actually strengths that we could use to support others in our community – Varden’s future community. I reconnected with my reo and te ao Māori; and the feeling of whanaungatanga that I once knew had returned.

Four years later, we find ourselves in our own home, on our own piece of whenua, entrenched in our culture, running our own wellbeing business and above all, Varden has a sense of connection. Varden is now a smiling, boisterous, affectionate and kind 9-year-old boy. He loves school, loves singing waiata, dancing and has achieved three things we never thought were possible. Going to the toilet, making himself a kai, and can say I love you – “I yuh yuu!”.

Over this time, I’ve also received a diagnosis of Asperger’s, and it has been one of the most powerful experiences that we have ever gone through as a whānau. It made a lot of things about my childhood make sense and it also gave us a deeper insight into the world that Varden lives in.

Now when I look at Varden, I realise that even though Varden isn’t a big talker, he speaks through his eyes and heart. Even though Varden isn’t a crowd person, he can make you feel like you’re the only person in the room. Even though Varden isn’t a big reader, he can read our wairua and know when we’re not right. And finally, regardless of the fact that Varden isn’t an academic by ‘normal standards’, he is a master in the art of manaakitanga; one smile can remind you of how important you really are to him.

Don’t give up! Takiwātanga is exactly that, people finding their own time and space. As a Māori whānau, we’ve realised that Varden’s journey is a taonga, a precious gift that that has taken us on our own pathway of whānau development and re-connection. When we look into Varden’s eyes, we don’t see autism, we see our boy, we see our taonga, we see our reason for still being here to tell the story, and above all we see him feeling a sense of whanaungatanga in his own time and place.

Turaukawa and Aimee Bartlett

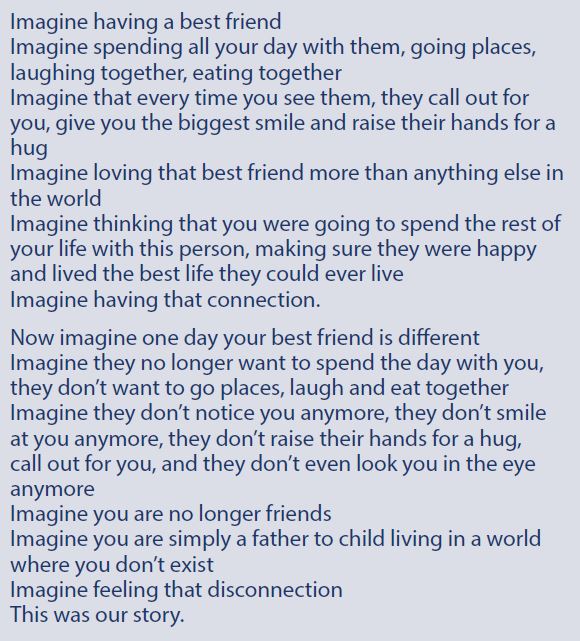

So imagine now that your best friend starts to recognise you again

Imagine they start smiling at you, and even give you the odd hug here and there

Imagine your best friend is now your little boy again

Imagine knowing that you’ll never be apart again

Imagine realising your grandmother saw something special in you, and knew one day you would use her teachings for a special purpose

Imagine realising that purpose was Varden…

Imagine that connection.

- Tūraukawa Bartlett is a specialist in hope and inspiration.

- He is a director of Manavation and a social influencer.

- Takiwātanga is a derivation of Keri Opai’s phrase for autism: “tōku/tōna anō takiwā” – “my/his/her own time and space”.

- This article first appeared in Altogether Autism Journal, Issue 2, 2019.