Despite being a well-established concept in the Autistic community, the phenomenon of Autistic burnout has only recently come to the attention of academic researchers. Rachael Wiltshire summarises the current research on Autistic burnout, explaining what it is and suggesting some strategies for recovery.

I have always had labels. By seven, I knew that I was shy, and I knew I was a worrywart. What I did not know at the time was that, even at that young age, the worrywart label had already taken on an official form: a generalised anxiety disorder diagnosis. The autism label followed five years later. It helped me find my place in the world as someone who was not shy or a worrywart, but simply different. Nevertheless, even the knowledge that autism explained my differences did not stop me accumulating more labels as I grew up: generalised anxiety disorder again in Year 10, major depression in my first year of university and every two to three years since then. Over time, I came to realise that my mental health just seemed to be cyclic — no matter what I tried, every few years things would come crashing down and I would have to start building back from scratch again. I learned that taking care of my mental health was a balancing act, walking a tightrope between keeping busy enough to not become overwhelmed with boredom, but not so busy that I left no time for rest.

Last year, whilst writing Altogether Autism’s Tertiary Guides, I stumbled across a new label. Perhaps my experience of cyclic mental health challenges was not separate to my Autistic identity at all. Perhaps what I was really experiencing was Autistic burnout.

What is Autistic burnout?

The advent of the internet enabled Autistic people to connect online, and discussions of a phenomenon named ‘Autistic burnout’ soon emerged in these spaces. Nevertheless, it is only in the past few years that researchers have started to pay attention to this phenomenon. Between 2020 and 2022, three papers were published which independently sought to define what Autistic burnout is (Higgins et al., 2021; Mantzalas et al., 2022a; Raymaker et al., 2020). Collectively, these studies suggest that Autistic burnout is characterised by exhaustion, withdrawal, loss of previously acquired skills and increased intensity of Autistic traits (such as stimming and sensory sensitivity). Burnout can have a significant negative impact on Autistic people’s lives: it is often chronic or recurrent, it may lead to the development of other mental health challenges such as depression and it is often associated with suicidal ideation.

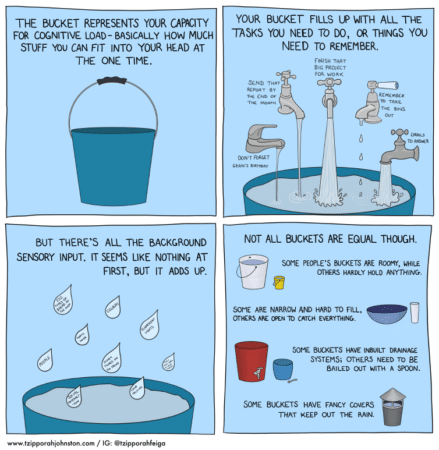

Autistic burnout is likely caused by the stress of living in a world that was not designed for our needs. Many Autistic people learn to mask; that is, we hide our true Autistic selves to navigate our way through a world built to neurotypical expectations. We might supress our stims, force ourselves to make eye contact and wear uncomfortable clothes to get and keep a job, make friends and participate in our communities. This takes significant cognitive effort: it is exhausting! Add in the background hum of an unfriendly sensory environment and everyday life stressors, and burnout is a predictable result. Autistic artist Tzipporah Johnston likens our brains to buckets: masking, sensory stimuli and everyday tasks fill your bucket up, and if it overflows, it fries your brain like a phone dropped in a puddle. This is burnout.

Image source: Creator Tzipporah Johnston, Buckets for Brains, via https://www.tzipporahjohnston.com/comics

Recovery

With research into Autistic burnout in its infancy, no studies have yet been published that investigate the effectiveness of different strategies for recovering from burnout. The following suggestions are drawn from my own experience, and the suggestions of participants in the studies that have sought to define Autistic burnout.

- Differentiate between burnout and other mental health challenges. Burnout can look similar to other mental health challenges, like anxiety or depression, but appropriate recovery strategies differ. In particular, reducing social and sensory demands is a useful strategy for recovering from burnout, whereas this type of avoidance is not seen as useful in treating anxiety and depression. As one participant in Mantzalas et al.’s (2022a) study explained:

“I was told for years that avoiding things will only make everything worse. And while that is commonly true for my anxiety it absolutely isn’t true for my autism related problems. Exposure there makes it WORSE because it causes overload, then burnout. Avoidance HELPS this.”

It is not always easy to tell Autistic burnout apart from other mental health challenges. Researchers have yet to develop any tools for doing so, and burnout can co-occur with challenges like anxiety or depression. However, some factors that may suggest burnout is the appropriate explanation include increased sensory sensitivity, a continued ability to find joy in one’s interests and it being possible to identify exhaustion from masking as the cause.

- Rest. Rest is the key to recovering from Autistic burnout, although it is of course not always easy to achieve. In some cases, months or years of rest might be needed and recovery may well look like a new normal, rather than returning to whatever your previous normal was. After all, if burnout is a sign that the demands of a neurotypical world have exceeded your ability to cope, recovery must look like changing those demands. Returning to the bucket analogy is helpful here: if you can proactively use rest to reduce social, sensory and task-related demands, you might manage to keep your bucket from overflowing. This might look like making sure to schedule time alone with your interests each day, for example. Some people who receive funded disability supports are able to employ someone to help them with tasks such as cleaning or meal preparation and find this frees up space in their brain that was previously devoted to managing those tasks.

- Predict when burnout episodes might be more likely and prepare accordingly. In my own experience, getting enough rest is a balancing act: going too far in the opposite direction and getting bored is also not great for my mental health. One strategy for maintaining this balance is to be aware of times when burnout is more likely and proactively increasing rest at these times. As a phenomenon of chronic overwhelm, burnout is more likely at times when demands increase. For example, many people recall that their first incidence of burnout occurred during adolescence or as they transitioned into adulthood. Thus, as part of planning for major transitions it makes sense to take steps to reduce the risk of burnout. For example, can you schedule more downtime into your week? Reduce social demands for a while? Set aside more time for engaging with your interests?

- Unmask. It is the effort of masking that makes Autistic people so vulnerable to burning out. Unfortunately, this does not mean that unmasking is a simple solution to preventing burnout. Indeed, masking is an adaptive strategy that helps us survive in the world and, in some situations, masking is essential to keeping people safe. However, finding safe times and places where it is possible to be your authentic Autistic self is a key part of recovering from and preventing burnout. Unmasking Autism by Dr Devon Price is an excellent resource for exploring unmasking safely in more depth.

Lessons from Burnout

Ultimately, Autistic burnout tells us two key things about the role of autism in society. First, it underscores the importance of continued efforts to destigmatise, and indeed celebrate, autism. As Mantzalas et al. (2022b) argue, Autistic burnout may be common, but it “should not be accepted as an inherent part of being Autistic.” In a world in which Autistic people were safe to unmask, with environments designed with sensory sensitivities in mind and understanding that people’s needs, abilities and priorities fluctuate, we would be much less likely to reach a state of cognitive overload, and more able to take the time out to recover when we did. Destigmatising autism to this extent will not be easy, but working towards it is essential to Autistic people’s wellbeing.

Second, the story of research into Autistic burnout reminds us of the importance of listening to Autistic voices. Mantzalas et al. (2022a) sought to define Autistic burnout by collecting internet discussion forum posts about it; the first reference they found comes from 2005. It would be another 15 years before anyone sought to define Autistic burnout in the academic literature. Think of where our understanding might be now if studies into Autistic burnout had commenced in the mid-2000s. Think of all the people whose lives might have been different if they had known that the key to dealing with their anguish was rest, not continuing to push through in the hope that it would get better. These are the people we fail when we fail to listen to Autistic voices.

Rachael Wiltshire is currently one of Altogether Autism’s Live Chat Agents / Researchers. She was previously an Autistic advisor on Altogether Autism’s Consumer Advisory Group.

References

Higgins, J.M., Arnold, S.R.C., Weise, J., Pellicano, E., & Trollor, J.N. (2021). Defining Autistic burnout through experts by lived experience: Grounded Delphi method investigating #AutisticBurnout. Autism, 00(0), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211019858

Johnston, T. (n.d.). Buckets for brains (a comic about burnout and cognitive load). Tzipporah Johnston. 567616_a2d17802bb1b43cbb074a1eee2b330b2.pdf (tzipporahjohnston.com)

Mantzalas, J., Richdale, A.L., Adikari, A., Lowe, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2022a). What is Autistic burnout? A thematic analysis of posts on two online platforms. Autism in Adulthood, 4(1), 52-65. What Is Autistic Burnout? A Thematic Analysis of Posts on Two Online Platforms | Autism in Adulthood (liebertpub.com)

Mantzalas, J., Richdale, A.L., & Dissanayake, C. (2022b). A conceptual model of risk and protective factors for Autistic burnout. Autism Research, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2722

Price, D. (2022). Unmasking autism: Discovering the new faces of neurodiversity. Harmony.

Raymaker, D.M., Teo, A.R., Steckler, N.A., Lentz, B., Scharer, M., Santos, A.D., Kapp, S.K., Hunter, M., Joyce, A., & Nicolaidis, C. (2020). “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: defining Autistic burnout. Autism in Adulthood, 2(2), 132-143. “Having All of Your Internal Resources Exhausted Beyond Measure and Being Left with No Clean-Up Crew”: Defining Autistic Burnout | Autism in Adulthood (liebertpub.com)