Sue Kinnear

28 February 2017 – Altogether Autism published its stance on the use of seclusion in schools (Issue 4, 2016, p.12). In the following article, Sue Kinnear, Wellington- based Special Education needs coordinator and a specialist teacher of autism, describes her implementation of a sensory room as respite from overwhelming situations for her students as an alternative to seclusion.

Educators aim for inclusion of all students in educational environments and meet their individual needs. How do we provide support for students with sensory and anxiety challenges when the classroom environment itself is the catalyst that affects their ability to process the stimuli that they are receiving?

Our role is to support students in the learning but how do we manage their personal challenges?

I was motivated to change in 2009 with the knowledge the following year three of my students would transition onto an Ongoing Resource Scheme.

The creation of a special environment at our Wellington intermediate school called a Sensory Room required us to work out the practice and facilitation of using it.

Background information collected from transition meetings and Sensory Profile Assessments identified that each of the three students had complex individual diagnoses including autism, and sensory sensitivities and anxiety.

The assessments made recommendations of how we could address and incorporate the sensory needs in a classroom environment within each of the student’s daily programmes.

The question was how to respond and provide support before, during and after the students’ emotions, anxieties and behaviours had reached extreme levels of personal distress.

In consultation with family and specialists, we decided that a room that might support sensory needs had the potential to support the students.

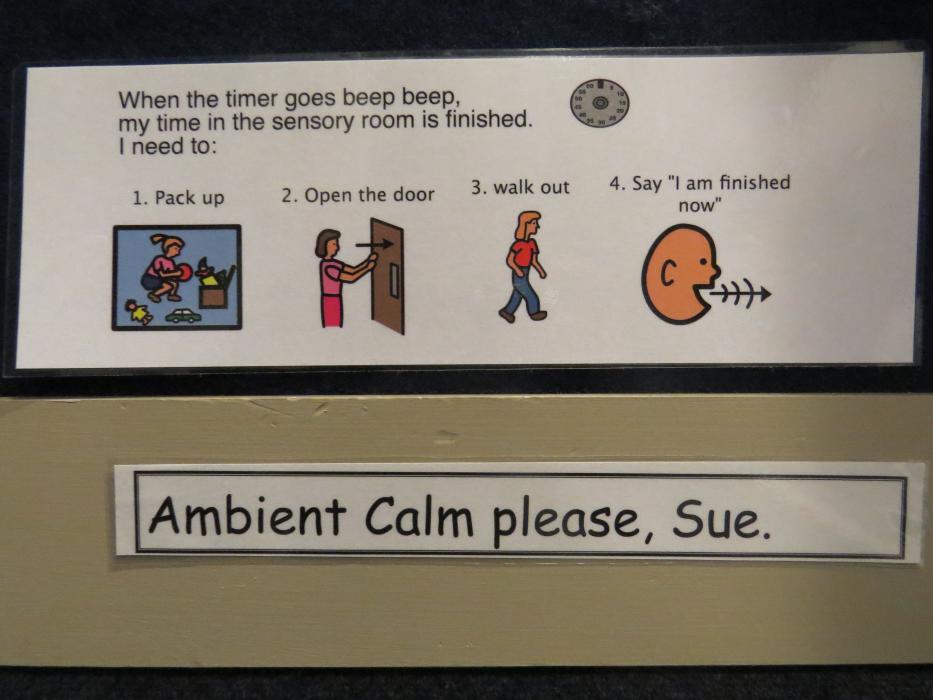

It became clear that I needed to develop procedures around the use of the room.

I made a conscious decision to use the title, “Sensory Room.” The role of multi-sensory rooms is to increase sensory awareness, often with lots of lighting effects. The title “Sensory Room” avoided the inference that multiple stimuli were the only option.

I had a clear vision. We had potential to support students with heightened levels of anxiety or sensory sensitivities.

I had four priorities:

- Establishing a relationship with the student

- Meeting the needs of the student

- Establishing clear expectations

- Encouraging the return to class and engagement in learning.

The aim was to contribute to the student’s understanding of their individual needs so that they could learn how to react and respond to their personal challenges with resilience and increase their abilities to “manage self”, New Zealand Curriculum key competencies (MOE. p.12).

Creation

Kinnear chose a navy colour for the room so students can minimise light

Multi-sensory rooms often use white walls to project lighting onto them. I decided to choose an alternative colour pallet of cream and navy. Rather than using a light colour on the walls, I decided that the floor, walls and curtains would be navy. I wanted students, if they wanted to, to have the ability to minimise light.

Playing DVDs with calming visual scenes such as nature, aquariums, beach walks or space adds lighting.

DVDs can also provide audio choices in volume and/or style of music or sound.

Soundproofing in the walls, ceiling and door allows an element of control over the level of sound from outside the room.

If people prefer to sit or lay on the floor the extra underlay and soft carpet allows you to do so comfortably. We modified the original building specifications to install a stronger support beam and higher quality metal fixtures to hold a swinging feature that can accommodate up to 200 kilograms.

The sensory room has two doors and students are able to exit either door at any given time. It is not a punitive room.

Skills of the facilitator

I identified the characteristics that I was displaying in the role as a facilitator and found it was necessary to work on the following:

- Develop a genuine relationship with the student

- Use short clear phrases

- Adapt the tone of your voice to each scenario

- Adapt your physical energy to each scenario

- Be aware of how you move

- Introduce visuals to increase communication if necessary

- Use redirection

- Encourage student advocacy.

All of these actions had an impact. You might think that success could be specific to one facilitator, but through a modelling and coaching process, I now have teacher assistants and teachers who also follow the same approach with equal success.

Facilitators encourage students to communicate their choices and action them whenever possible. If the student’s preference is to use a calming DVD, they are encouraged to turn the equipment on and begin the choice process.

Redirection of attention can have a positive impact on a student’s emotions and physical energy. It may also contribute to a feeling of control and autonomy.

We reviewed expectations of positive behaviours. Students are encouraged to set time frames and these range from 10-minute breaks up to 20-minute breaks. The students understand that they will return to their classroom or a quiet space of choice to re-engage in learning.

The facilitator leaves the sensory room and sits within sight of the small viewing window. The safety of the student is paramount and facilitators are responsible for supervision. At the end of the session, the facilitator gently knocks on the door to alert the student that someone is entering the room and that transition back to the classroom is about to begin. If the lights are off, we take care to introduce the light gently by using the dimmer switch.

When is it used?

The use of our sensory room is flexible and focussed on the needs of the individual. We examine patterns of events, triggers and behaviours. Some students struggle with the transition between arriving at school and heading into class. Some students struggle with the transition into the classroom following lunch breaks.

The sensory room may be booked in advance or negotiated when needs arises.

A number of students have used our sensory room regularly. Observations highlighted that the majority of students preferred to control, reduce, or limit the stimuli they were receiving.

Systems and management development

I have created two key documents regarding the use of the sensory room. We have a “Procedures Manual” which outlines key procedures, the philosophy, the booking system and equipment. The second document is a “Sensory Room Response Evaluation” sheet used to collect data on the frequency and duration of student use, their preferred set up and their responses to the intervention.

Is this inclusive?

Some may consider this intervention as non-inclusive. Is it possible to provide controlled sensory experiences and still have inclusion within a community?

Fowler (2008) poses an interesting perspective. Being included and controlling one’s sensory experiences do not have to oppose each other. Our goal is to meet individual specific needs and to encourage positive transition back into the classroom.

Effectiveness of the intervention

Reflective practitioners are encouraged to examine practice and critically review the interventions recommended and implemented. Critical revision of Snoezelen and of multi-sensory rooms by Research Autism (2013) and Texas Statewide Leadership for Autism Training (2009) identified that neither of these are an evidence-based intervention and require further research.

A revised edition of New Zealand Autism Spectrum Disorder Guidelines was completed in 2016. Part 3: Education for learners with ASD identifies that a positive strategy of providing a quiet space or area and allowing, “regular, timetabled ‘down time” could have benefits for young people with autism (p.119).

At our school, if a student feels that the classroom does not provide a quiet enough space for them, they have the option of accessing the sensory room as an alternative space.

The autonomy of students is encouraged. We aim to develop students’ skills and their ability to manage their personal challenges. The Specialist Service standards refer to the three principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, partnership, protection and participation. We have an area that is well thought out, and adaptable. We provide effective, caring, support and guidance. We aim to support and maintain student presence at school.

Heightened states of sensory processing and behaviours because of anxiety, stress and frustration are challenging. We explore the function of behaviours. The student response evaluation sheets gather data and they identify trends of frequency, preferences and feedback for each student using the sensory room.

This data informs practice. Macfarlane (2003) recommends schools have an opportunity to develop a strong ethic of caring (manaakitanga) and attending to each student, not just for the head but also for the heart as well providing a “safe haven classroom” (p. 97).

I believe our decision to go ahead with a room is supported by Pere’s (1991) concepts of holistic well-being: taha tinana, (physical well-being), hinengaro, (the mind), mana ake, (the uniqueness of each individual) and mauri, (life force/energy) within the Maori health model, Te Wheke. The integration of this intervention is student-focussed.

Observable and anecdotal evidence from facilitators, class teachers, parents and students indicated that for numerous students we have been able to address sensory and anxiety concerns and the intention is that we will continue to do so in the future. (1, 646 words) LIMIT 1700

Sue Kinnear (B.Ed, P.G.Dip.Sp.Tchg – Autism) is a Special Education Needs Coordinator and a Specialist Teacher of Autism, currently working at an Intermediate in the Greater Wellington district.

This article was first published in Altogether Autism Journal Issue 1, 2017 read the latest edition.

References

Fowler, S. (2008). Multisensory Rooms & Environments: controlled sensory experiences for people with profound and multiple disabilities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. London. United Kingdom and Philadelphia, United States of America.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. Learning Media, Wellington, New Zealand.

Ministries of Health and Education. (2016). New Zealand Autism Spectrum Disorder Guideline. Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/nz-asd-guidelineaug16v2_

0.pdf

Macfarlane, A. H. (2004). Kia hiwa ra! Listen to culture: Maori student’s plea to educators. Wellington: NZCER.

Pere, R. (1991). Te Wheke: A celebration of infinite wisdom. Gisborne: Ao Ako.

Research Autism (2013). List of Interventions. Retrieved from

http://researchautism.net/autism_treatments_therapies_interventions.ikml

Research Autism. (2013). Multi-sensory environments and autism. Retrieved

From http://researchautism.net/autism_treatments_therapies_intervention.ikml?ra=164

ROMPA International. (2016). Multi Sensory Rooms. Retrieved from http://www.rompa.com/snoezelen-sensory-rooms.html

Texas Statewide Leadership for Autism Training. (2009). Texas Guide for Effective Teaching Adaptive Behaviour Assessments. Retrieved from www.txautism.net/docs/Guide/Evaluation/AdaptiveBehavior.pdf

Texas Statewide Leadership for Autism Training. (2009). Intervention summary. Retrieved from

http://www.txautism.net/uploads/target/InterventionSummary.pdf